An asset, in its broadest conception, is a resource or entity that bestows future economic boons to its possessor, be it an individual, a corporation, or a nation. While traditionally anchored in a company’s financial statements, the concept of assets now embraces a wider spectrum in the financial domain. This treatise delves into the multifaceted nature of assets, spanning financial assets to those harboring future economic worth.

Defining Assets

Assets encompass items or resources imbued with economic value, promising prospective monetary gains to their owners. These can include liquidity-maintaining assets or those sold for profit. Typically, assets are quantified in monetary terms, assessing their liquidity or profit potential.

Assets owned by an individual are termed personal assets, whereas those under company or corporate ownership are business assets.

Assets serve multiple purposes: they augment net worth, elevate business valuation, and more. Spanning the tangible (like gold) to the intangible (such as Bitcoin), assets are instrumental for individuals and corporations in demonstrating solvency, financial robustness, and equity. They can be leveraged for loan security or sold for profit. Business success likelihood often hinges on the equation of total assets minus liabilities.

Assets could be a resource like manufacturing equipment or a patent, poised to generate future cash flow.

Categorization of Assets

Assets bifurcate into various types, including current assets, fixed assets, both tangible and intangible assets, operating assets, and non-operating assets.

Asset Functionality

Assets are amassed by individuals, companies, and governments with the anticipation of yielding economic benefits, either in the short or long term. However, assets do not guarantee gains, as their value can appreciate or depreciate, impacting sale value and overall solvency.

Solvency suggests that held assets are adequate to manage or settle outstanding liabilities. Balance sheets, delineating current assets, liabilities, and equity, are employed by companies to gauge asset adequacy against liabilities. Before venturing deeper into the asset realm, let’s scrutinize the prevalent asset types.

Asset Varieties

Assets, vast in definition, fit into multiple classification categories. These are the predominant asset types:

Current Assets (business assets)

Current assets, swiftly convertible into cash (liquid assets), are utilized for timely bill payment or liability settlement. Examples include cash and equivalents, accounts receivable, inventory, or prepaid expenses.

Fixed Assets

Fixed assets, or non-current assets, denote long-term investments (exceeding 12 months) and are not readily liquidated into cash. They harbor future economic value, with examples being land, buildings, or equipment.

Tangible Assets

Tangible assets, physical in nature, encompass items like cash, inventory, buildings, stock, machinery, or furniture.

Intangible Assets

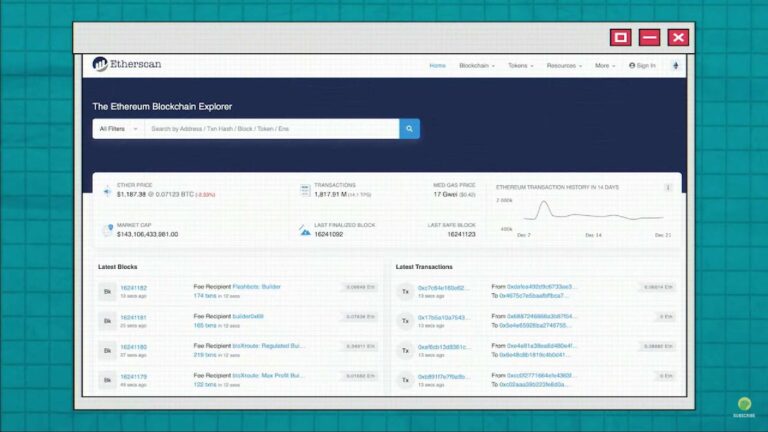

Intangible assets, lacking physical substance and visibility, include intellectual property, patents, cryptocurrency, licenses, grants, and secret formulas.

Operating Assets

Operating assets, owned for daily business operations or revenue generation, include inventories, patents, equipment, secret formulas, and licenses.

Non-operating Assets

Non-operating assets, not primarily used for business activities, may yet yield future profits. Examples are vacant land, marketable securities, short-term and long-term investments.

Nuances of Asset Definition

The asset definition, though expansive, doesn’t fully encapsulate their potential. For instance, patents, though intangible, are crucial operating assets for some businesses.

Bitcoin, a digital, intangible asset, could also be a current or liquid asset.

Inventory exemplifies a current, tangible, operating asset, demonstrating the fluidity of asset categorization.

Assets vs Liabilities

In assessing an entrepreneur’s net worth or a company’s value, liabilities are pivotal in determining solvency. The Fund Balance (Net Assets or Equity) is calculated by subtracting liabilities from assets.

To ascertain a company’s fund balance, scrutinize its balance sheet, which varies depending on its public or private status, with public entities mandatorily disclosing balance sheets in annual reports.

In essence: Assets – Liabilities = Equity

Understanding Asset Economic Value

The asset definition is boundless, extending even to inheritances like a sapphire necklace, which could be a current and tangible asset. Its value could be immediately capitalized on or enhanced during a sapphire scarcity.

This article aims to elucidate the nuances and similarities in assets’ roles within personal and professional contexts.

Assets, fundamentally, are resources or items anticipated to generate cash flow for an individual, business, or government. Whether as fixed or current assets, the acquisition’s ultimate goal is to derive profit. Assets, encompassing gold, Bitcoin, houses, cars, secret formulas, and patents, rightfully belong in this category due to their potential to translate into cash-equivalent value.

Diversifying Portfolio with Asset Allocation

Asset allocation, a crucial strategy in portfolio management, entails diversifying investments across various asset categories to optimize returns while managing risk. This approach balances the portfolio by spreading investments across different asset types, such as equities, bonds, real estate, and cash. Understanding the interplay of these asset classes is key to effective portfolio diversification.

Equities (Stocks)

- Nature: Represents ownership in a company;

- Risk and Return: Higher potential returns but with increased volatility;

- Ideal for: Investors seeking growth over the long term.

Bonds (Fixed-Income Securities)

- Nature: Loans to governments or corporations with fixed repayments;

- Risk and Return: Lower risk than stocks, offering steady income;

- Ideal for: Investors looking for stability and income.

Real Estate

- Nature: Investment in property, either directly or through REITs;

- Risk and Return: Medium risk with potential for both income and capital appreciation;

- Ideal for: Those seeking a balance of income and growth, with a tolerance for real estate market fluctuations.

Cash and Cash Equivalents

- Nature: Highly liquid assets like bank deposits, Treasury bills.

- Risk and Return: Low risk with minimal returns, primarily used for liquidity.

- Ideal for: Investors prioritizing safety and liquidity over growth.

Commodities

- Nature: Physical goods like gold, oil, agricultural products;

- Risk and Return: Can be volatile; influenced by market and geopolitical factors;

- Ideal for: Investors looking to hedge against inflation and diversify beyond traditional stocks and bonds.

Conclusion

Understanding assets is crucial for effective financial planning and wealth building. This exploration highlights the importance of recognizing various asset types, from tangible to intangible, and their strategic allocation in a diversified portfolio. Assets like equities, bonds, real estate, and alternative investments, each with their unique risks and rewards, are key to creating a resilient and tailored investment strategy. As the financial landscape evolves, a deep understanding of these instruments is essential for anyone aiming to achieve financial security and success.